This morning I noticed that the color of the woods are slowly turning as the leaves offer their first hint that season’s change is coming soon. A few days ago a new fawn joined the family of deer that enjoy an evening snack outside our door. And last week I drove to the Lowe’s in Waynesboro all by myself.

That’s a bigger deal than you think.

Like any sixteen-year-old growing up in rural Pennsylvania I loved the freedom that having my drivers license represented. But I don’t know that I ever loved driving. It was a skill I needed if I wanted to get from home to Becky’s house, or choir rehearsal, or to Bake Oven Knob. I was never afraid of driving but it was less of a joy and more of a necessary chore. It always made me a little nervous.

I didn’t become afraid of driving until four years ago when my black Honda CRV, with me behind the wheel, was rammed from behind at a red light and totaled on Oregon Expressway just a minute away from my former home in Palo Alto. After that accident, an accident in which I was not injured, being in a car left me hyper-vigilant, white knuckled and close to panic. It was almost tolerable when I was behind the wheel but deepened when I was a passenger. Behind the wheel I had some control. As a passenger all control was relinquished.

This fear had a huge and controlling impact on my life. I missed art exhibits in San Francisco I was desperate to see. I turned down party invitations and gatherings with friends. I said ‘no’ to going to the movies. I avoided almost every event where driving was involved even when my heart wanted something different. But to go anywhere required time for me to prepare mentally.

There were exceptions, of course. A two-hour drive with a friend to attend an art workshop was doable because I had time to talk myself down from the edge. I had support from my friend who commiserated with my fear and who assured me that the SUV she was driving was an indestructible tank. And then there was the drive Ben and I made up the Pacific coast to Sea Ranch. The deep anxiety I experienced navigating the twisty, fog shrouded road on the final leg of our journey there was the price I paid for an exceptionally beautiful weekend on the sunlit ocean’s edge.

But this was no way to live. I was determined to leave my fear behind in California. I was not going to allow my fear of driving to control my life in Virginia.

About a month ago I made my first trip to the Harris Teeter Market two miles down Rockfish Gap from our new home. And even though when I leave Harris Teeter I have to make a left hand turn onto what can sometimes be a somewhat busy two-lane road, I survived. I’ve been going to Harris Teeter a few times a week ever since. Even when we don’t need anything. Just for the practice.

My next challenge arrived ten days ago when Ben needed to catch the train to DC. He offered to Uber to the station but I insisted we take the car. I wanted the challenge of navigating my way home. I could do that. Or I could shake off a little fear. I chose the latter and set Waze for the nearest Whole Foods. And again, I survived. I also survived two days ago when his train arrived back in Charlottesville and I was there to meet him. I can’t remember the last time I was there to meet Ben after a business trip. I didn’t know how much I missed doing that.

Remember when you were sixteen and you passed your drivers test? That’s how going to Whole Foods, doing the food shopping and then driving the twenty minutes home felt to me. That’s how finding my way to the train station felt. That’s how going to Dollar General and then all the way to Waynesboro felt. Such simple, ordinary things. Still, it was as if someone was handing me the literal car key to my freedom. That someone was me.

I still have some ways to go. I haven’t driven to Charlottesville ‘proper’ or navigated finding parking near the Pedestrian Mall. But I know that I will. There are too many things I want to do. Too many experiences I no longer want to put on hold.

Do you have a fear you’ve been trying to shake? What steps could you take to begin letting go of that fear?

It’s like a dream. The only reason why I know for certain I was there is because of the sense of familiarity that welled inside when I saw images of the protests that occurred in Kerala in early January. A

It’s like a dream. The only reason why I know for certain I was there is because of the sense of familiarity that welled inside when I saw images of the protests that occurred in Kerala in early January. A  Our ten days in Kerala were a first for Ben and me. Over the past five years we’ve enjoyed time spent with family back east and long weekend breaks to Half Moon Bay and

Our ten days in Kerala were a first for Ben and me. Over the past five years we’ve enjoyed time spent with family back east and long weekend breaks to Half Moon Bay and  For those two days my brain turned the volume down on the endless chatter, my body relaxed in a way I didn’t think was possible, and Ben and I had a chance to bask in the love we share. We engaged with life, with the world around us and with each other. During those two days I was fully immersed in the life around me – the colors, the textures, the sounds and even the silence. I engaged with life, not with a computer.

For those two days my brain turned the volume down on the endless chatter, my body relaxed in a way I didn’t think was possible, and Ben and I had a chance to bask in the love we share. We engaged with life, with the world around us and with each other. During those two days I was fully immersed in the life around me – the colors, the textures, the sounds and even the silence. I engaged with life, not with a computer. Winding our way down from Munnar to sea level the sky gradually shifts from blue to milk white. Not white like creamy full fat milk – more like the water-downed milk I remember from childhood. The milk I drank at Mrs. Dietrich’s kitchen table when I was a kid was so fresh and warm from the cow that she served it to her daughter and me on ice. As the ice melted the milk became thin and pale. That’s the color of the sky as we descend from Munnar.

Winding our way down from Munnar to sea level the sky gradually shifts from blue to milk white. Not white like creamy full fat milk – more like the water-downed milk I remember from childhood. The milk I drank at Mrs. Dietrich’s kitchen table when I was a kid was so fresh and warm from the cow that she served it to her daughter and me on ice. As the ice melted the milk became thin and pale. That’s the color of the sky as we descend from Munnar. Women wrapped in colorful sarees ride side-saddle on scooters while on the road’s shoulder ancient men wrapped in lungis tucked in above their knees push carts balanced on bicycle wheels and piled high with wares.

Women wrapped in colorful sarees ride side-saddle on scooters while on the road’s shoulder ancient men wrapped in lungis tucked in above their knees push carts balanced on bicycle wheels and piled high with wares. The four hour drive from Munnar to Alleppey is long and hot and bumpy but when we arrive at the houseboat all of that is forgotten. For the rest of the afternoon and into the first part of the next morning we’ll be on the longest lake in Kerala. We’re in a traditional houseboat. It moves almost without sound. I can hear the lapping of water and once again the sound of birds calling to one another. There’s an immense variety of bird life here – brahminy kites that look like bald eagles, kingfishers, parrots, flycatchers, darters, cormorants, egrets and herons all greet us as we move through the waters.

The four hour drive from Munnar to Alleppey is long and hot and bumpy but when we arrive at the houseboat all of that is forgotten. For the rest of the afternoon and into the first part of the next morning we’ll be on the longest lake in Kerala. We’re in a traditional houseboat. It moves almost without sound. I can hear the lapping of water and once again the sound of birds calling to one another. There’s an immense variety of bird life here – brahminy kites that look like bald eagles, kingfishers, parrots, flycatchers, darters, cormorants, egrets and herons all greet us as we move through the waters.  The lake is life and livelihood for the people who live along its edge. Children are ferried home from school in wooden boats. Women wash clothes while their kids play in its waters. At sunrise lone fishermen, silhouetted in their small canoes by the red dawn, make their way to where they hope will be the day’s best catch.

The lake is life and livelihood for the people who live along its edge. Children are ferried home from school in wooden boats. Women wash clothes while their kids play in its waters. At sunrise lone fishermen, silhouetted in their small canoes by the red dawn, make their way to where they hope will be the day’s best catch.

The sunlight in Kochi is diffused by heavy, moist air. The December heat keeps my skin sticky and my ankles puffed. But it’s a beautiful light – intense and muted at the same time. It brightens colors and softens the edges of the Chinese fishermen nets that, since the 14th century, have pulled fish from Kochi’s harbour. The nets are fascinating structures built from teak and bamboo. They’re cantilevered and require nothing more than the weight of a man to lower themselves into the water.

The sunlight in Kochi is diffused by heavy, moist air. The December heat keeps my skin sticky and my ankles puffed. But it’s a beautiful light – intense and muted at the same time. It brightens colors and softens the edges of the Chinese fishermen nets that, since the 14th century, have pulled fish from Kochi’s harbour. The nets are fascinating structures built from teak and bamboo. They’re cantilevered and require nothing more than the weight of a man to lower themselves into the water. Along the embankment men dressed in lungis, their heads wrapped in wet and frayed cloth as protection against the sun, prepare to sell the fish whose gills still move, desperate to find water. Interspersed between the fishmongers are stalls filled with wares available to purchase for the tourists fresh off cruise ships in port from Mumbai and Singapore. Follow the cobbled path from the nets to the jetty and you’ll find fish for your supper, leather belts, straw hats, toy tuk-tuks for the kids at home, plastic pasta makers and hand-held sewing machines the size of a stapler.

Along the embankment men dressed in lungis, their heads wrapped in wet and frayed cloth as protection against the sun, prepare to sell the fish whose gills still move, desperate to find water. Interspersed between the fishmongers are stalls filled with wares available to purchase for the tourists fresh off cruise ships in port from Mumbai and Singapore. Follow the cobbled path from the nets to the jetty and you’ll find fish for your supper, leather belts, straw hats, toy tuk-tuks for the kids at home, plastic pasta makers and hand-held sewing machines the size of a stapler. Nearby is a respite. The Church of Saint Francis is a short walk from the jetty. Built in 1503 and the original burial place of Vasco de Gama, it is a beautiful but unassuming building.

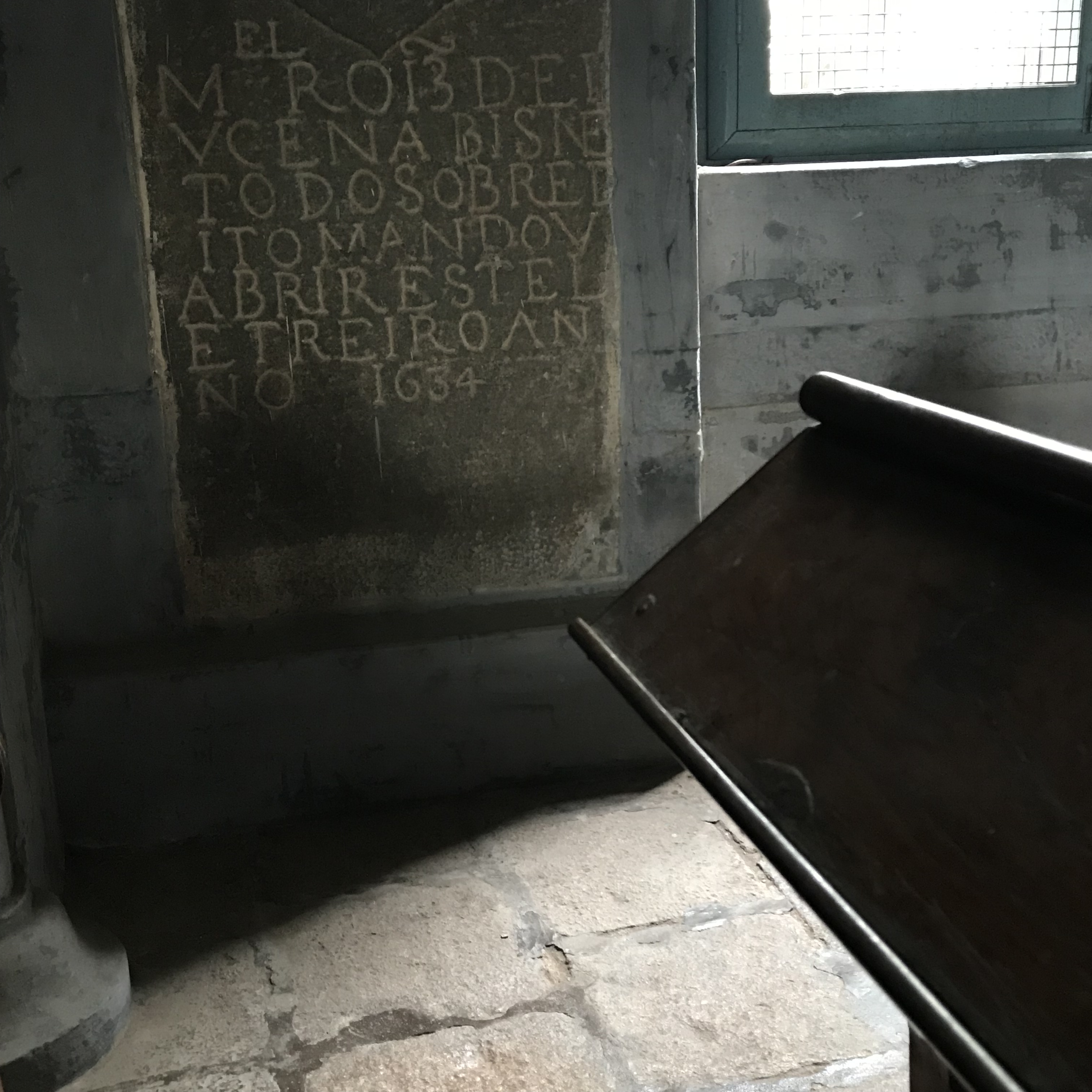

Nearby is a respite. The Church of Saint Francis is a short walk from the jetty. Built in 1503 and the original burial place of Vasco de Gama, it is a beautiful but unassuming building. Its stone interior, lined with dark wooden pews, is cooled with a mechanism built of rope, pulleys and embroidered fabric attached to poles that run the length of the nave. The poles are lowered and when they swing the congregation is fanned by the movement of the fabric.

Its stone interior, lined with dark wooden pews, is cooled with a mechanism built of rope, pulleys and embroidered fabric attached to poles that run the length of the nave. The poles are lowered and when they swing the congregation is fanned by the movement of the fabric. The first two close calls were flukes. It was only after I saw my life pass before my eyes for the third time that I began to question our sanity. By the time we were in our fifth hour of winding switchbacks on a road so narrow we frequently stopped to accomodate traffic barreling down the steep grade toward us I knew we were doomed. We were headed toward a former hill station in Munnar now named Windermere Estate.

The first two close calls were flukes. It was only after I saw my life pass before my eyes for the third time that I began to question our sanity. By the time we were in our fifth hour of winding switchbacks on a road so narrow we frequently stopped to accomodate traffic barreling down the steep grade toward us I knew we were doomed. We were headed toward a former hill station in Munnar now named Windermere Estate. It’s beautiful here. The air is warm but fresh and we awoke this morning to the song of the red whiskered bulbul and not the noise of car horns. From a vantage point reached by climbing a set of stairs cut into stone we have a view of mist covered tea plantations, deep valleys and a rugged mountain ridge on which, we’re told, wild elephants sometimes roam into view.

It’s beautiful here. The air is warm but fresh and we awoke this morning to the song of the red whiskered bulbul and not the noise of car horns. From a vantage point reached by climbing a set of stairs cut into stone we have a view of mist covered tea plantations, deep valleys and a rugged mountain ridge on which, we’re told, wild elephants sometimes roam into view. Our one day at Windermere is a day of rest. The grounds of the estate are too beautiful to contemplate leaving. With the exception of one short walk to a small village just below the estate grounds, we are content to watch the world go by from the little porch attached to our room.

Our one day at Windermere is a day of rest. The grounds of the estate are too beautiful to contemplate leaving. With the exception of one short walk to a small village just below the estate grounds, we are content to watch the world go by from the little porch attached to our room.